SAAP-148, a powerful new weapon against drug-resistant bacteria inspired by the human body

How do you cure bacterial infections that can not be controlled with antibiotics?

This is possible with peptides: short chains of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

The Leiden University spin-off Madam Therapeutics reports that researchers from the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), Academic Medical Center (AMC) and the Association of Dutch Burn Centers have published on this subject in the scientific journal Science Translational Medicine.

As part of a European research consortium ”Biofilm alliance” (BALI), they have tweaked a naturally occurring peptide found in the human body. By doing so, the researchers have designed a drug that could wipe out obstinate microbes resistant to available antibiotics.

In an editorial comment on the website of the scientific journal Science, Dr Kim Lewis, a microbiologist at the Northeastern University in Boston who was not involved in the work says that the candidate adds “an important piece … to the puzzle of creating a perfect antibiotic”.

When a small subset of bacteria survives antibiotic treatment an infection can get out of control fast. As these resilient microbes thrive, they can group together on a surface—like a wound or a medical device—and encase themselves in a slimy protective layer known as a biofilm. Such biofilms are hard for drugs to penetrate, and they harbor dormant cells called persisters that toleratean antibiotic assault only to come roaring back later. Such infections “can be horrible for patients,” says immunologist Dr Peter Nibbering at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

The team of Dutch collaborators are trying to combat these biofilm-associated infections by improving on a human peptide called LL-37, which play multiple roles in the body’s immune response. LL-37 displays bacteria-killing abilities, and the researchers previously shortened the peptide to make a more powerful variant, consisting of 24 of the 37 original amino acids. In the new work, they optimized this peptide by making a series of random replacements to its building blocks without disrupting its overall tertiary structure.

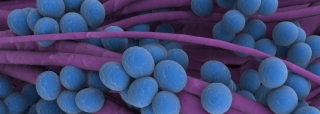

One variation, dubbed SAAP-148, proved a powerful weapon, the team reports in Science Translational Medicine. Whereas most traditional antibiotics target specific groups of bacteria and kill by disrupting key mechanisms of those microbes, SAAP-148 is more of a generalist. It kills by damaging most any bacterium’s plasma membrane, causing it to spill its contents and deflate.

SAAP-148 eradicated drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter baumannii biofilms successfully —two leading causes of hospital-acquired infections that often defy available treatments — from human skin samples and infected wounds on the backs of mice. It also managed to knock out persister cells in a bacterial biofilm that had already been treated with the antibiotic rifampicin, often used to fight persistent infections at the site of prostheses.

“This is the first published demonstration of the killing of such persisters”, notes Prof Bob Hancock, a microbiologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, in the editorial comment on the website of Science.

SAAP-148 also appears to overcome what Hancock calls “one of the big bedevilments” of antibiotic candidates: The environment of the human body inhibits the activity of many such molecules because they stick to proteins and lipids in the blood. SAAP-148 looks to be one of the few known peptides that kills bacteria efficiently without also binding to these circulating obstacles in serum, he notes.

Nibbering and colleagues also report that bacteria didn’t manage to develop resistance to SAAP-148 after repeated exposures. That’s surprising, says Dr Tim Tolker-Nielsen, a microbiologist at the University of Copenhagen’s biofilm research center in the editorial comment, though he notes that resistance could still develop under different conditions.

In partnership with the researchers, Madam Therapeutics is pursuing SAAP-148 to treat amongst others, skin wound infections, bladder infections, or infections at the site of prostheses. To administer the drug systemically, the team is also working on the design of an injectable formulation that protects the peptide from breaking down in the body, makes it more selective, and directs it to the site of infection inside the body.

Madam Therapeutics expects to test SAAP-148 in clinical trials soon—first to disinfect lesions from the inflammatory skin disease atopic dermatitis, then to treat patients suffering from diabetic foot ulcers as well as burn patients.